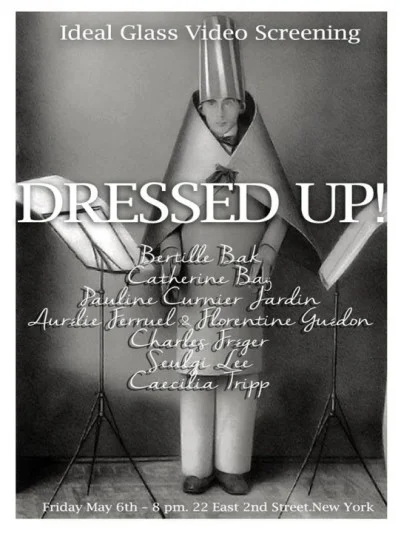

Dressed Up!

DRESSED UP!

Taking the costume––one of Ideal Glass’ landmark––as a starting point, this art video screening gathers videos in which clothing motivates the argument and, often time, even acts as a character in itself. Celebrating the centenary of the Cabaret Voltaire and its outrageous taste for grotesque dresses, this program aims to reinvest the subversive power of the costume, its direct expressivity and the strong emotional impact it can have on the viewer.

If regular clothes are the space of projection of the real self, the costume is the space of projection of the imagined-self. Some of the works presented at the screening investigate the costume’s nature as a way to transform themselves, such as Ferruel & Guédon who invent their own rituals and costumes to re-consider folklore. In Vis voluntatis (2009) Charles Fréger––whose entire body of work is centered on dress customs––gets carried away in a Chinese dance and by doing so conforms to the traditional dress and make-up. The costume plays a significant role in the process of deciphering a character. Typically in comedia dell’arte, the figure is the costume (and vice versa) to the point that it becomes increasingly difficult to determine who is in action: the actor or the clothes? Pauline Curnier Jardin embarks her crew in a thrilling circus, in which regular characters––the ringmaster and acrobats for instance––mixes with ideas personified through costumes. Bertille Bak’s video piece is also built around that concept while her dressed-actors are animated like puppets. Another strong power of outfits is that wearing the costume is being the costume: Caecilia Tripp follows participants to the Trinidad Carnival as they are getting dressed in the streets and progressively become historical characters, engaging themselves in an empowering re-enactment as a decolonizing Act. Catherine Baÿ dresses her performers as Snow White and sends them in public space, with instructions to adopt troubling behaviors. Baÿ reminds us that the costume is, above all, an object of communication: to reach its efficiency, it requires an audience to blend the spectacular and the ordinary.

In his essay The Diseases of Costume (1955), Roland Barthes outlines a moral of the theater costume, as he believes that it is based on the deep meaning of the play or its gestus, which it is meant to serve. In these videos, the costume stands as the exact contrary: it doesn’t serve any other mission than itself, it glows, it catches the eye, it concentrates the attention and distracts from everything else. The costume is used per se and is served by the action. It is more than a sign; it is the idea itself. The trial of truth is exalted in the videos presented at Ideal Glass: the costume escapes from the stage and measures itself to streets and the fields.

Come as you are – you might leave as someone else!

Works by:

Bertille Bak

Catherine Baÿ

Pauline Curnier Jardin

Aurélie Ferruel & Florentine Guédon

Charles Fréger

Seulgi Lee

Caecilia Tripp

Bertille Bak

(Born in 1983 in France, she works in Paris, France)

Bertille Bak’s multi-disciplinary practice revolves around the creation of films addressing the notion of community and identity and evoking a “tribal adventure” through which she tells stories about the communities she seeks out. Since her initial experience in 2007 within the mining community of Barlin in France, Bak has continued to immerse herself within micro-societies––sensitive to the situation of these communities, she appropriates with affection and humor these ethical systems and popular traditions. If the results of her “infiltrations” convey the aesthetic of ethnographical documentary, some picturesque elements and other incongruities lead these realistic stories towards semi-fictional portraits. From New York’s Polish community to the Din Daeng’s neighborhood in Bangkok or the French convent in Paris, Bak portrays with sensitivity and humor the broader life within these communities––mixing truths and falsehoods and playing with how the clichés and fantasies that we have of these populations resonate with us. (Source: Nettie Horn gallery website)

Catherine Baÿ

(Based in Paris)After studying theater (École Jacques Lecoq, Philippe Gaulier, Antoine Vitez), ethnology (Jean Rouch) and dance (Marcia Barcello, Philippe Decouflé, Milly Nichols), Catherine Baÿ spent about 10 years developing her work as a choreographer and director. Her work has led her to experiment in different forms (choreography, performing, directing, video, cabaret), and to collaborate with artists from various disciplines. From 1987 to 1994, Baÿ orchestrated performances and events in various spaces, such as swimming pools, nightclubs, vacant lots, and in the galleries of Yvon Lambert and Anne de Villepoix. She collaborated with plastic artists (Combas, Jean-Charles Blais, Sylvia Bossu), architects (Laurence Bourgeois, Pascale Lecoq), and dancers/actors (Alain Rigout, Amy Garmon et Laurence Levasseur), among others.

Since 1994, she has been developing a body of work specific to the codes of representation. In Relief ou le discours sur l’éloquence, she dissects the distances between the intimate versus social body while observing political men’s postures during the 1995 French presidential elections. Ainsi parlait Eliane et Lulu, developed with Marco Berrettini and Kolatch, plays on the confrontation of unique bodies on stage. In 1999, she choreographed Nains mode d’emploi, a show that takes place in a display window, in which Baÿ elaborates on a complex stage device that establishes a dialog between a video screen and the actors, exacerbates the clown motif, and concentrates on the satirical approach of the world of choreography.(Source: Snow White project website)

Pauline Curnier Jardin

(Born in Marseille, France, in 1980, she works in Netherlands)

Through drawing, performance, music, installation, and film, Pauline Curnier Jardin crafts fictional adventures full of chance occurrences and wonders that nonetheless carry with them the potential for mishap or misfortune. Through lighting, color, texture, costume, soundtrack, and props, she creates transgressive, funny, and highly stylized visual settings that owe more to theater than to conventional narrative cinema. Curnier Jardin’s stories reveal a fascination with monsters, decorative objects, and animals, although her work expresses a particular awareness of the roles women have played in mythology, folklore, and conventional narrative cinema, roles that are commonly stereotyped as saint, witch, mother, or mystic.

Curnier Jardin supports a generous, intelligent, non-systematic vision of continuity between human and nonhuman bodies. Usually associated with femininity and passivity, she looks to passion—traditionally opposed to “masculine” reason—as primary to sensations, perceptions, and the subject’s—or object’s—potential for action. (Alise Upitis)

Aurélie Ferruel and Florentine Guédon

(Born in 1988 and 1990, they work in France)

Aurélie Ferruel and Florentine Guédon have been working together since 2010. In this collaboration, they share their ideas, readings and technical knowledge to develop exclusively a common, mutual production. Their body of work ranges from sculpture, video, installation and performances: the installations are never static. At the origin of their work is a shared interest for tradition, as a generational link, transmitter of actions and knowledge. The family members play an important role in their practice, whether by the transmission of technical skills or by participating directly in their performance. Their goal is not to advocate the preservation of traditions, but to observe their evolution, their shapes, their reactivations or reinventions.

The group is a way for the individual to build an identity, working in duo helps forge this desire to belong and to develop a collective representation through objects such as costumes, headdresses, jewelry, etc. Many accessories are loaded with a strong ceremonial value. Beside their family cultures, their plastic work integrates and mixes identity codes of various groups such as tribes, local fraternities, various social circles. The two artists observe as anthropologists and take ownership of cults and aesthetical traditions to create new ones. (Source: artists’ website, translation: Marie van Eersel)

Charles Fréger

(Born in 1975 in France, he works in Paris, France)

Charles Fréger has been seeking to establish a collection entitled Portraits photographiques et uniformes (Photographic portraits and uniforms), a series captured in Europe and across the world devoted to groups of people (students, soldiers, sportsmen, etc.) that focuses on what they are wearing: their uniform. His first series within that body of work was called Faire face (To face) as the meeting of the photographer and the model takes the form of a subtle clash to better appreciate the substance of a being in the world and its belonging to a social body.

Charles Fréger has chosen communities for which outfits take on their most sparkling and prestigious appearance (Steps, Empire, Opera) as well as the more modest ones where the corporate image epitomizes life in Europe (Bleus, Sihuhu) or on other continents (Umwana, Ti du). Ceremonial regiments and troops of western elites rub shoulders with Rwandan orphans or Vietnamese monks where the exotic dress doubles as an almost ethnographic vision, close to that of August Sander. In his work, he makes sure to present his subjects in harmony with a place, a time and a community as if to better convince us of our implacable ties to the excesses of appearance and the social aspect of position or status. Charles Fréger explores the genre of the portrait as an artist, constantly looking back at history. (Source: artist’s website)

Seulgi Lee

(Born in Korea in 1972, she works in Paris, France)

Since relocating to Paris from Seoul more than twenty years ago, Seulgi Lee has developed a unique artistic practice immediately recognizable for its use of color, gesture, simple yet elegant forms, and performance. In spite of (or perhaps linked to) its deference to bright, cheerful color, Lee has described her sculptural practice as utilitarian, invariably related to the power, fragility, and contingency of the body: her works are tools, to be available at-hand, used by those who are nearby. Culled from everyday belongings, masks, and pedestrian objects, these artworks frequently employ a vocabulary more readily used to describe craft, and challenge arbitrary distinctions between mannered, formal sculptural syntax and a more popularized design or craft aesthetic. (Mélanie Bouteloup)

Caecilia Tripp

(Based in Paris)

Using means of filmic installation, photography as well as performance, Caecilia Tripp’s work is entangled with the “play of the trickster”. With references to cinematic codes using forms of “re-enactment” and “rehearsals” it emerges into the space of collective imagination as a space of transgression of social and cultural boundaries. Beyond geographical borders and with a critical eye it deals with forms of freedom, utopia and civil disobedience at the crossroads of globalization, shining a light on the invention of new languages, sounds, cultural codes and social imaginary as a permanent process of “making history”.

Caecilia Tripp has received several international grants representing a body of film and video installations, performance and photographic works from 1999 up to now, which has been shown internationally in galleries, museums such as PS1/MOMA New York / USA, Palais de Tokyo Paris /France, Jeu de Paume Paris / France, Museum of Modern Art, Paris, etc.

The Making of Americans (2004) won the award for the best experimental film at Cinema Paradise, Hawai / USA. It was screened at several international festivals and museum venues. (Source: artist’s website)